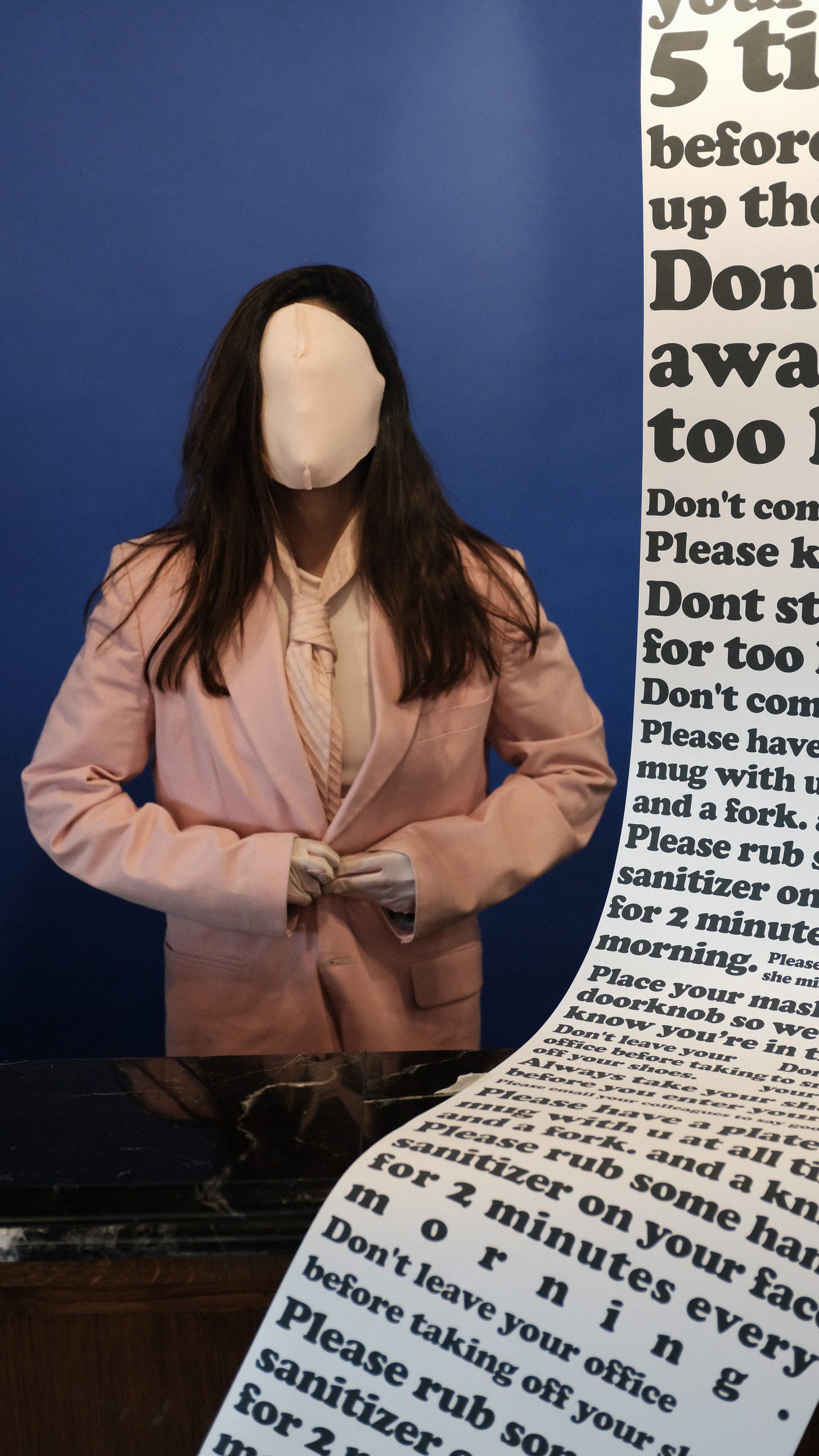

Authenticity and Emotional Labour in a Post-Covid Era

An 'awakening' journey [my contribution to 'Light Bulb Moments & the Power of Critical Thinking' by Gloria Moss & Katherine Armitage]

Coming from a working-class English background, and living a transient life in council estates, my schooling was disjointed to say the least. Unsurprisingly, I left with little in terms of what others define as ‘meaningful qualifications’. But paradoxically, maybe because of the mainly poor-quality teaching I had endured, I harboured a secret desire to teach. It was this idea that motivated me to restart my learning journey later in life, after years of boredom from commercial-sector work in what Graeber defines as Bullshit Jobs (Graeber 2018). Being a ‘mature, part-time, female student’ at a ‘top’ ‘Russell Group’ UK University was an interesting experience during the early 2000s. Blair had declared his Government’s top three priorities as ‘Education, Education, Education’ and I was apparently in a ‘target group’. The University wasn’t entirely onboard with this New Labour thinking; scheduled evening seminars were inconvenient.

Many adults are emotionally scarred by the childhood division and prejudice caused by an archaic English Grammar school system, myself included [1].

[Image Victoria Museum via UnSplash]

It wasn’t until years later, studying a foundation module of my social studies degree, aged 30, that I was shocked to discover how the whole education system had been (and continues to be) rigged against females. Perhaps even more worryingly, so many people, my parents included, were totally unaware of the mechanisms at play. For instance, the questions within an 11+ exam are not culturally-competent and girls needed to obtain higher marks than boys in order to achieve a formal ‘pass’. So, relegated to the local Catholic Comprehensive, I was thus denied the early qualification pathway towards teaching, a career journey that was actively encouraged for my friends at the Grammar School for Girls. Perhaps it was then, more than twenty years ago now - since I am in my fifties - that my worldview began to shake slightly.

Whilst studying further and becoming acutely aware of the corruption deep in the machinery of our society, I worked in a public health research centre. Here, I witnessed for the first time, how an ‘academic’ paper could be manipulated and edited [described further below]. For, as a humble secretary, I remember being instructed by a senior academic to create a ‘new’ academic paper about an intervention for patients, by using ‘copy and paste’ from the body (not the literature review) of an article previously published in a different journal. ‘Surely this can’t be how it’s done?’ I asked myself naively. But it was.

Ten years later, when I had completed my PostGrad Teaching Diploma, I was teaching adults at a city-centre refugee centre, and at Further Education (FE) colleges in the Midlands. These institutions provided insights into the way that education funding policies were seen as hurdles to jump, by (non-teaching) management. Authentic, positive student experiences were often perceived as less of a priority, compared to the bureaucracy that surrounded these experiences. By manipulating the methodologies, language and timing of student feedback and learning outcomes, the data could be presented in a more positive light. Hence funding requirements that sustained income for staff in flash, glass-fronted buildings were built on a house of cards. The reality is, not all students’ learning outcomes are ‘measurable’ in a quantitative way – to claim otherwise is simply absurd. Occasionally, I would connect with like-minded teachers also frustrated by the lack of authenticity in the teaching and learning policies, some were also concerned about the dumbing-down of student activities that risked developing students’ critical-thinking skills. The influence of New Public Management (NPM) in education was in full-swing during this time and led to my interest in the impact of NPM on our classrooms. Specifically, I investigated the concept of emotional labour as it relates to adult education (Edgington 2016a).

[photo by Jorge Percival on Unsplash]

To explain briefly (because it’s relevant to understanding my current situation), the term ‘emotional labour’ was originally used by Hochschild to describe the performance or ‘performativity’ of customer-service work. She gave the example of airline cabin-crew whose job demands that staff convey certain attitudes (Hochschild 1983).

[Photo by Suhyeon Choi on Unsplash]

Hochschild argued that these paid jobs are exploitative because it is inherently unethical and shaming to expect those undertaking manual labour to combine this labour with the projection of what appear to be (but may not be) ‘genuine’ emotions. She went further in stating that, in contrast to practical skills, the more authentic (or ‘human’) these paid-for emotions are perceived to be, the more these individuals are sought-after and valued. In a corporeal example, Hochschild observed how a staff member reacted when a passenger suffering from air-sickness, vomited onto her uniform. In contrast to exhibiting understandably authentic emotions (revulsion, frustration, disgust), the crew-member smiled broadly and reassured the customer that the stinking mess was ‘no problem at all.’ The concept of emotional labour then, has profound implications today for a generation encouraged to ‘fake it ‘til you make it'.

My research confirmed how the phenomenon of emotional labour also exists in Further and Higher Education institutions (FE/HE). It showed, for instance, that when staff ‘perform’ within their teaching roles they must compromise, or even betray, their personal values in order to adhere to (sometimes illogical or even unethical) rules and regulations. Four common (if somewhat ‘taboo’) examples of such ‘unofficial’ FE/HE policies (that I have witnessed) include:

Recording a student as ‘present’ on arbitrarily ‘important’ term-dates when in fact the student was absent/withdrawn from a course (because ‘attendance’ ensures continued course funding).

Encouraging students to record positive feedback on their course evaluations, because the outcomes from these ‘surveys’ are reflected in the University’s profile ‘score’ and hence their potential future employment prospects.

Not producing transparent assessment grading criteria and thereby enabling students’ assignment outcomes to be ‘reviewed’ in the light of the cohort’s results.

On being notified of an imminent (Government) inspection eg teaching and learning observations (UK FE, Ofsted), educational institutions instructing their staff to remove any poor quality/incomplete assignments from the spotlight and to send ‘difficult’ students on short-notice work-placements.

Within these four examples, we can see how staff’s emotional labour can artificially prop up the (fake) image of an institution’s integrity. This emotional labour can contribute to effective marketing campaigns, producing financial funding and fulfilling contrived auditing requirements. In fact, their enactment becomes a ‘necessary evil’ in order to retain employment because negative consequences ensue for those individuals unwilling to comply with such coercive policies. Not only can non-compliance lead to alienation and the painful emotion of shame, it can lead to punitive measures such as a lack of promotion opportunities, or even termination of an employment contract and with that, the person’s career and vocation (The Secret Professor 2022).

This is extremely serious since emotional labour is far from being innocuous. In my own research, the dangers of this performativity on the individual were evidenced in the form of harms to mental health and wellbeing, when individuals are forced to stray too far, too often, from their authentic Self (Edgington 2016b). A teacher’s sense of shame can manifest in acts of compliance that produce a feeling that they are sacrificing fundamental elements of what teaching and learning is really about. As I later learned, the concept of shame was exploited by Government agencies, which are victims of regulatory capture in ensuring compliance with the recent Covid legislation. For instance, the behavioural science report Mindspace set out recommendations for effective marketing campaigns by Government and specifically commended the use of images/phrases that could encourage feelings of shame, thereby triggering public compliance with authoritarian policies (Dolan et al. 2010).

[Photo by Mindspace Studio on Unsplash]

It was following my immigration to New Zealand in 2013, nearly nine years ago, that I discovered the true extent of the regulatory capture and with that, the conflicts of interest and the power of the unwritten Corporate Playbook. For example, censorship and propaganda are used to Dismiss, Delay, Deny, Discredit, Deflect, Deceive and Divide anyone who dares to ask inconvenient questions. The New Zealand taxpayer-funded aerial poisoning of our forests with the highly toxic synthetic poison, sodium monofluoroacetate (1080) has been regularly repeated for over 65 years, despite widespread public condemnation and evidence of harms (e.g. McQueen 2017). And as I investigated the inconsistencies between the New Zealand Government’s narrative that presented this poison as ‘safe and effective’ and the stark scientific realities of this poison, (its lethal instability has caused it to be banned or severely restricted in most other countries) the influence from BigChem became obvious.[2]

That is not all, since just a cursory scrape beneath the surface illuminates how lacking in transparency the scientific peer-reviewed process is, on the topic of 1080 poison use in New Zealand. Articles that get through the censorship filter to publication, are often methodologically flawed and missing essential (human and animal) ethics approval. Moreover, there are often contradictions between research outcomes and conclusions, presumably to appease the funders of the research. The authors perhaps hope that few people will bother to read more than the abstract and in the rare event that a reader does spot the contradictions and complain, the usual, highly effective Corporate Playbook can easily be set in motion once again.

[image of 1080 poisoned food-baits being aerially distributed via helicopter, source People’s Inquiry 2020 NZ]

Generally speaking, the academic literature on emotional labour discusses the performance of ‘positive’ emotions such as building rapport and establishing trust, understanding and empathy, observing how these are exemplified in sectors like healthcare, education, sales, customer-service, hairdressing and even sex-workers’ roles (eg Price 2001). But what of the emotional labour that emphasises the opposite of those emotions – for example the disdainful or hostile emotions towards an artificially defined ‘outgroup’ (for an interesting example, see Hockey, 2009)? Furthermore, if that same emotional labour promotes a political narrative that is not based on fact, but rather on an ideology, it can lead to dangerous discrimination. I believe this type of embedded emotional labour, if unchecked, promotes illogical disinformation and becomes a societal norm which can develop into totalitarianism (Desmet 2022).

Reflecting now on the somewhat unfulfilling jobs from my early career, and my later experiences in Further and Higher Education, I can see parallels between my various roles and what lecturers who I interviewed for my PhD research described. For they spoke of carrying out pointless duties that essentially were an exercise in ‘jumping through hoops’. Examples included writing contrived lesson-plans that did not reflect the reality of that session’s teaching, and submitting the plan after a session had taken place.[3] Truth to tell, the distorted definitions of ‘best practice’ in all sectors of teaching and learning - highly controversial for decades - are widely accepted as having been hijacked for a political agenda (The Secret Teacher 2016). And it’s not a coincidence that these educational whistle-blowers are often anonymous. Many individuals have suffered poor health and even committed suicide, trying to align with nonsensical procedures (Adams 2015), procedures that Government agencies regularly admit are meaningless (Ofsted 2012).

However, just as the Covid policy responses such as lockdowns and vaccine mandates are authoritarian and fundamentally flawed (eg Alexander 2021), many staff feel it necessary to maintain compliance by continuing to offer their emotional labour in delivering, or at least remaining unquestioning of, so-called ‘best practice’ teaching and learning. Caught between a rock and a hard place, some academics feel they must comply in order to retain professional employment, personal recognition and associations with institutional integrity (Honneth 2004). High levels of personal debt – ironically partly a consequence of Blair’s promotion of HE, to a population which without student loans, simply couldn’t afford it – also provide effective blackmail that coerce staff to comply.

In contrast to undertaking roles that demand compliance, many researchers have highlighted genuine, or authentic human interactions in education. For example, James and Diment (2003) investigated what they described as ‘underground teaching’ in UK Further Education. The researchers observed student/teacher interactions that took place away from any managerial surveillance, that were honest, rewarding and intellectually challenging. But I can’t help wondering whether in using the phrase ‘underground teaching’, these authors were complicit in downgrading and marginalising the value of this work. After all, why should the emotional labour offered by teachers in fulfilment of their official duties (the stuff that ticks the various boxes) be ‘valued’ - whilst simultaneously their authentic interactions with their students remain hidden? Since when did our education system become so Orwellian as to relegate any teaching and learning that happens outside the gaze of Big Brother?

Interestingly, these experiences of genuine learning and teaching may have become even more prevalent during Covid ‘lockdowns’ when institutions forced policies of distance-learning (McKie 2020). This situation permitted unregulated interactions with students online, sometimes outside the ‘endorsed’ Virtual Learning Environment (VLE) platforms, and in time-frames not explicitly ‘measurable’, and this may have led to meaningful opportunities for greater authenticity. This is significant since authentic teaching and learning - by its very nature - is creative and does not conform to prescribed curricula, disciplines and institutional policies (Vickers 2010). These interactions could be an antidote to so-called ‘bullshit jobs’ and their associated emotional labour. That may be because they include truth telling: an acceptance of uncertainty within genuine human connectivity (Desmet 2022).

I have described some examples of how NPM has impacted negatively on teaching and learning policies. In addition to these negative aspects, it is worth pointing out that many elements of (well-established) academic emotional labour in HE in fact fits with Graeber’s definition of a ‘bullshit job’. For instance:

Paraphrasing an already-published article for submission to another journal, because various academic ‘brownie-points’ are gained with each research ‘output’;

Re-working research data outcomes that were collected decades ago (in another context), in order to publish something ‘timely’;

Gaining kudos of contrived ‘impact’ (eg ‘reTweets’) by using BigTech social media platforms to ‘disseminate’ research outcomes to Joe Public;

Manipulating an article’s citations to include one or more names of those listed on a specific editorial board, prior to submission to that journal;

Exploiting PhD students with (ill-advised?) ambitions to be employed within academia, to write a ‘co-authored’ article that supports his/her government-funded academic-supervisor’s theory…and so the list goes on.

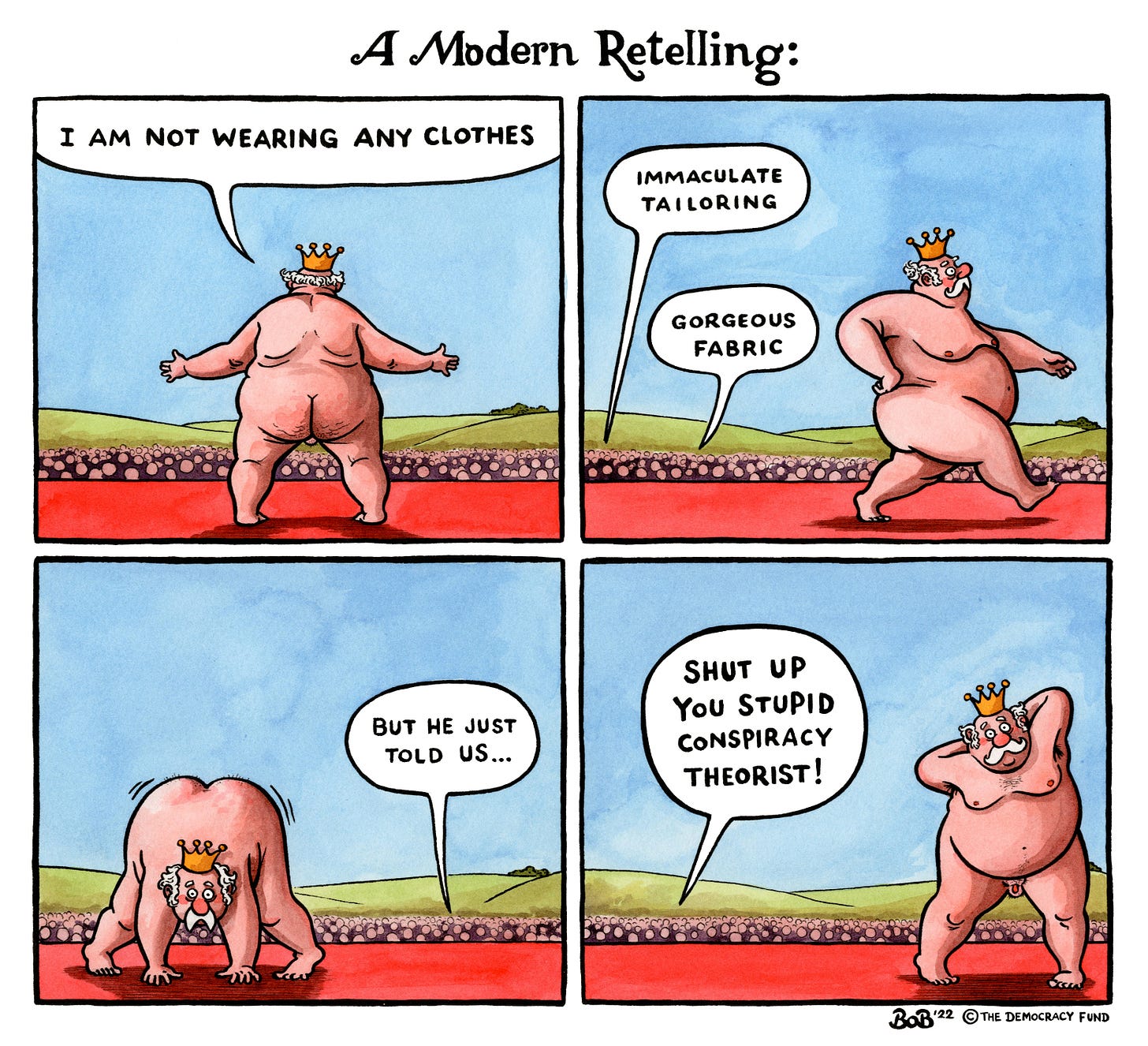

Far from being a ‘critical conscience of society’ then, our universities have lost all integrity and credibility as meaningful and ethical education institutions. This is not due to incompetence or laziness. Over several decades, the valid outcomes from numerous research projects have been systematically suppressed. Evidence-based discussions of climate change, toxicology, democratic rights, gendered roles, colonial history, best practice leadership (Secret Professor, 2022) and many other topics are off-limits because arguments that differ from the political narrative have been conveniently labelled ‘conspiracy theories’ or ‘misinformation’. Researchers who have dared to question their censorship, have been faced with the overwhelming corporate power that is now being exposed to Joe Public (The Secret Professor 2022; Shir-Raz et al. 2022).

In 2020 the disturbing deceptions I had previously uncovered in the aerial poisoning of New Zealand’s forests were repeated in the contradictions between Government narratives and the scientific evidence about Covid and then the ‘vaccines’. The only difference was that this time the narrative was global and the phraseology and timescales were in lockstep.

In July 2021, many sleepless nights resulted from my effort to come to terms with the way in which my world had shifted on its axis. The increasingly dystopian world that I inhabited saw the mainstream media regularly engaged in reporting the exact opposite of the factual information concerning Covid ‘cases’, hospitalisations and deaths. World leaders would repeat the same phrases, over and again as if this was a neuro-lingustic programming (NLP) session. How could this be allowed? It was a re-telling of the Emperor has no Clothes, with numerous people waiting for the child to laugh out loud. But that laugh never came.

Days, weeks, months rolled by. By this time, I had left social media (Twitter/Facebook) since those platforms were replete with BigPharma propaganda and much of what I wrote was censored. This shadow-banning meant that I didn’t get to see genuine friends and family posts and there was outgroup hatred too, including shills and trolls. It was an unbearable, toxic environment.

I retained my well-established Linkedin profile and made some new connections with others who were speaking out. In October 2021, I saw a post that included Professor Norman Fenton, Queen Mary University, London, talking on Zoom to another academic about all-cause mortality data and the manipulation of statistics by the UK Government.[4] After an exchange of emails, we agreed to chat via Zoom and I vividly remember the relief of discovering (at some Godforsaken hour NZ-time) that I wasn’t going insane, and that there were very credible academics who felt they had been let down by colleagues (and Governments) and that we were living in a parallel universe.

It was conversations with academics like Norman, and investigations of research without conflicts of interest, that slowly caused me to regain my confidence and emotional strength. What I needed was that elusive authenticity that has become a constant theme in my life [5]. It was in that spirit of authenticity that in December 2021 I shared an article on Linkedin from the British Medical Journal (Thacker, 2021) and my profile on Linkedin was immediately suspended for ‘going against community policy’. I realised then, that the Corporate Playbook had matured into a sinister monster and that the suppression of the truth was ubiquitous, across all BigTech platforms.

Little wonder that academic’s ‘authentic’ blogging on non-censored platforms like Patreon and Substack has increased exponentially in the last two years. In my own case, blogging has provided a measure of catharsis for the traumatic challenges that we now face. Yes, technocracy and totalitarianism work in partnership, and algorithms, propaganda and censorship (including self-censorship) can cripple authentic communications and divide society. However, it is human nature to discover creative ways to overcome these challenges; exposing the Corporate Playbook is one way of doing this.

This post-Covid era presents an exciting future of opportunities for educationalists like myself. For many years, we have been ‘swimming against the tide’, sharing understandings about how fundamentally broken our education systems are. None of us wants a return to ‘normal’ (even if that were possible). Ethical educationalists aspire to facilitate learning in an atmosphere of mutual trust, in environments free from regulatory capture. Independence from conflicts of interest allows learning to be practical and contextualised, materials free from bias towards corporate profits or political ideologies and policies that are not skewed towards funding streams. Here, learners’ ‘screen time’ with digital avatars are erased in favour of meaningful, authentic, face-to-face communication. There’s a growing awareness of how this holistic, student-centred learning experience is a crucial part of our future.

This goal is not an idealistic fantasy. In the school sector, the transformation has already gained significant ground; in New Zealand, parents and guardians home-schooling have increased substantially in the past two years [6]. Kids are taken out of state schools partly in protest at the Governmental overreach, but also for other valid reasons. Many are adopting their own, community home-schooling groups, including creating private mini-libraries and joining the well-established global ‘un-schooling’ movement (Gatto, 2009).

[Photo by Kelly Sikkema on Unsplash]

Now it is time for universities to rise to the post-Covid challenge to provide authentic, student-centred learning. Communities which value democratic rights demand higher-level learning organisations that are without the boredom and restrictions of academic bureaucracies and Government qualification frameworks I describe above. As The Truth University [7] sets out, students can be equipped with genuine critical thinking skills, through high standards of intellectual engagement and innovative curricula free from outside influence or agendas. Re-envisaging and re-creating authentic university education for lifelong learning is an historic and well-overdue paradigm-shift and humanity needs this change urgently.

This extract from the book Light Bulb Moments and the Power of Critical Thinking has been republished with permission. Please support the Freedom Movement by buying a copy of this book and passing it on. either from Amazon or via the Truth University Press via their website, or email the Truth University directly: infotruthuniversity@protonmail.com

References

Adams, R. (2015) ‘Headteacher Killed Herself after Ofsted Downgrade, Inquest Hears’. The Guardian, 20 Nov.

Alexander, PA. (2021) ‘More Than 400 Studies on the Failure of Compulsory Covid Interventions (Lockdowns, Restrictions, Closures)’. Meta analysis, UK: Brownstone Institute. https://brownstone.org/articles/more-than-400-studies-on-the-failure-of-compulsory-covid-interventions/.

Desmet, M. (2022) The Psychology of Totalitarianism. London, UK: Chelsea Green.

Dolan, P. Hallworth, M. Halpern, D. King, D. & Vlaev, I. (2010) ‘Mindspace: Influencing Behaviour through Public Policy’. Discussion Document. Cabinet Office. London, UK: Institute for Government. https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/MINDSPACE.pdf.

Edgington, U. (2016a). Emotional Labour & Lesson Observation: A Study of England’s Further Education. Springer.

Edgington, U. (2016b). ‘Performativity and the Power of Shame: Lesson Observations, Emotional Labour and Professional Habitus’. Sociological Research Online 21 (1)

Gatto, J.T. (2009) Weapons of Mass Instruction: a schoolteacher’s journey through the dark world of compulsory schooling. Gabriola Island, BC, Canada: New Society Publishers.

Graeber, D. (2018) Bullshit Jobs: A Theory. New York, USA: Simon and Schuster.

Hochschild, A. (1983) The Managed Heart: Commercialisation of Human Feeling. Berkley, CA. USA.: University of California Press.

Hockey, J. (2009) ‘“Switch on”: Sensory Work in the Infantry’. Work, Employment and Society 23 (3): 477–93.

Honneth, A. (2004) ‘Recognition and Justice’. Acta Sociologica 47 (4): 351–64.

James, D. & Diment, K (2003) ‘Going Underground? Learning and Assessment in an Ambiguous Space’. Journal of Vocational Education and Training 55 (4): 407–22.

McKie, A. (2020) ‘Covid-19: Universities Treating Staff in “Vastly Different Ways”’. Times Higher Education Supplement, 20 April 2020

McQueen, F. (2017) The Quiet Forest. New Zealand: Tross Publishing.

Ofsted. (2012) ‘Press Release: Ofsted Announces Scrapping of “Satisfactory” Judgement in Move Designed to Help Improve Education for Millions of Children’, 2012.

Price, H. (2001) ‘Emotional Labour in the Classroom: A Psychoanalytic Perspective’. Journal of Social Work Practice 15 (2): 161–80.

Shir-Raz, Y., Elisha, R. Martin, B. Ronel, N. and Guetzkow, J. (2022). ‘Censorship and Suppression of Covid‑19 Heterodoxy: Tactics and Counter‑Tactics.’ Minerva Nov.

Thacker, P. (2021) ‘Covid-19: Researcher Blows the Whistle on Data Integrity Issues in Pfizer’s Vaccine Trial’. BMJ 375 (2635)

The Secret Professor (2022) The Dark Side of Academia: How Truth Is Suppressed. eBook. UK: The Truth University.

The Secret Teacher (2016) ‘I See Ofsted for What It Is – a Purposeless Farce’. The Guardian, 20 Feb.

Vickers, M. (2010) ‘The Creation of Fiction to Share Truths and Different Viewpoints: A Creative Journey and an Interpretive Process’. Qualitative Inquiry 16 (7): 556–65.

[1] In some counties of England during this time, entry to Grammar School offered a potentially higher-level academic education than that provided by the parallel comprehensive school system; entry was gained via a test taken at eleven years old, hence the term ‘11+’.

[2] For an excellent peer-review of the literature on 1080, see the work of Dr J Pollard et al. at https://1080science.co.nz/

[3] Management accepted how these ‘planning’ documents were simply a paper-exercise for auditing purposes.

[4] Details of this research available on the Professor’s website: normanfenton.com

[5] For instance, see reachingpeople.net for some ideas about debating skills using authenticity.

[6] Eg Homeschoolers increase by 80% in New Zealand after a pandemic Times of India 17 Oct 2022.

[7] www.truthuniversity.co.uk including https://truthuniversitycouk.uk/truth-university-interviews/ See also The Secret Professor (2022) pp.192-195.Light Bulb Moments and the Power of Critical Thinking

I experienced the same crazy double think even in my blue collar industrial job. Despite the OSHA safety training that paper masks don't stop asbestos which is bigger than a "virus", my coworkers became insistent on wearing them.

"The evolutionary psychologist William von Hippel found that humans use large parts of thinking power to navigate social world rather than perform independent analysis and decision making. For most people it is the mechanism that, in case of doubt, will prevent one from thinking what is right if, in return, it endangers one’s social status. This phenomenon occurs more strongly the higher a person’s social status. Another factor is that the more educated and more theoretically intelligent a person is, the more their brain is adept at selling them the biggest nonsense as a reasonable idea, as long as it elevates their social status. The upper educated class tends to be more inclined than ordinary people to chase some intellectual boondoggle. " -Sasha Latypova

'Dismiss, Delay, Deny, Discredit, Deflect, Deceive and Divide'.

Aren't alliterations just wonderful?

Division, Despair, Disinformation, Dependency, Depopulation, Deindustrialisation, Drugs, Death, signs of the times.

Education and educashon are no longer synonyms, just unrelated homophones.

Critical thought appears undesirable, inconsistent with the maintenance of a lie or concealment of the truth. Such is educashon.

Thank you for an excellent and educative article.